Thucydides on political intrigue in the divided city of Corcyra caused by the “desire to rule” (5thC BC)

About this Quotation:

Thomas Hobbes lived through the English Revolution (or Civil War) during the 1640s and 1650s so it is not hard to see his translation of civil revolt in Greece in the 5th century BC in light of his own experiences. In this quotation we read of the motives of the various factions in the divided city of Corcyra, all motivated by the “desire to rule” at all costs, revenge and “rapine”.

Other quotes from this week:

- 2007: Frank Chodorov argues that taxation is an act of coercion and if pushed to its logical limits will result in Socialism (1946)

- 2006: J.S. Mill was convinced he was living in a time when he would experience an explosion of classical liberal reform because “the sprit of the age” had dramatically changed (1831)

- 2005: In Joseph Addison’s play Cato Cato is asked what it would take for him to be Caesar’s “friend” - his answer is that Caesar would have to first “disband his legions” and then “restore the commonwealth to liberty” (1713)

Other quotes about Presidents, Kings, Tyrants, & Despots:

- 2010: Livy on the irrecoverable loss of liberty under the Roman Empire (10 AD)

- 2009: Jefferson feared that it would only be a matter of time before the American system of government degenerated into a form of “elective despotism” (1785)

- 2009: Lao Tzu discusses how “the great sages” (or wise advisors) protect the interests of the prince and thus “prove to be but guardians in the interest of the great thieves” (600 BC)

- 2009: Macaulay argues that politicians are less interested in the economic value of public works to the citizens than they are in their own reputation, embezzlement and “jobs for the boys” (1830)

- 2009: Althusius argues that a political leader is bound by his oath of office which, if violated, requires his removal (1614)

- 2009: Richard Overton shoots An Arrow against all Tyrants from the prison of Newgate into the prerogative bowels of the arbitrary House of Lords and all other usurpers and tyrants whatsoever (1646):

- 2009: St. Augustine states that kingdoms without justice are mere robberies, and robberies are like small kingdoms; but large Empires are piracy writ large (5th C)

- 2008: Lord Acton writes to Bishop Creighton that the same moral standards should be applied to all men, political and religious leaders included, especially since “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely” (1887)

- 2008: Edward Gibbon gloomily observed that in a unified empire like the Roman there was nowhere to escape, whereas with a multiplicity of states there were always gaps and interstices to hide in (1776)

- 2008: Thomas Hodgskin wonders how despotism comes to a country and concludes that the “first step” taken towards despotism gives it the power to take a second and a third - hence it must be stopped in its tracks at the very first sign (1813)

- 2008: George Washington warns that the knee jerk reaction of citizens to problems is to seek a solution in the creation of a “new monarch”(1786)

- 2008: Plato warns of the people’s protector who, once having tasted blood, turns into a wolf and a tyrant (340s BC)

- 2007: George Washington warns the nation in his Farewell Address, that love of power will tend to create a real despotism in America unless proper checks and balances are maintained to limit government power (1796)

- 2006: After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 John Milton was concerned with both how the triumphalist monarchists would treat the English people and how the disheartened English people would face their descendants (1660)

- 2006: Benjamin Constant argued that mediocre men, when they acquired power, became “more envious, more obstinate, more immoderate, and more convulsive” than men with talent (1815)

- 2005: Thomas Jefferson opposed vehemently the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798 which granted the President enormous powers showing that the government had become a tyranny which desired to govern with "a rod of iron" (1798)

- 2005: John Milton laments the case of a people who won their liberty “in the field” but who then foolishly “ran their necks again into the yoke” of tyranny (1660)

- 2005: Adam Ferguson notes that “implicit submission to any leader, or the uncontrouled exercise of any power” leads to a form of military government and ultimately despotism (1767)

- 2005: Edward Gibbon believed that unless public liberty was defended by “intrepid and vigilant guardians” any constitution would degenerate into despotism (1776)

- 2005: Montesquieu states that the Roman Empire fell because the costs of its military expansion introduced corruption and the loyalty of its soldiers was transferred from the City to its generals (1734)

- 2005: John Milton believes men live under a “double tyranny” within (the tyranny of custom and passions) which makes them blind to the tyranny of government without (1649)

- 2005: Vicesimus Knox tries to persuade an English nobleman that some did not come into the world with “saddles on their backs and bridles in their mouths” and some others like him came “ready booted and spurred to ride the rest to death” (1793)

- 2004: James Bryce believed that the Founders intended that the American President would be “a reduced and improved copy of the English king” (1885)

- 2004: Thomas Gordon believes that bigoted Princes are subject to the “blind control” of other “Directors and Masters” who work behind the scenes (1737)

- 2004: Algernon Sidney’s Motto was that his Hand (i.e. his pen) was an Enemy to all Tyrants (1660)

- 2004: Thomas Gordon compares the Greatness of Spartacus with that of Julius Caesar (1721)

3 March, 2008

| Thucydides on political intrigue in the divided city of Corcyra caused by the “desire to rule” (5thC BC) |

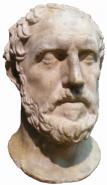

In his Third Book of his History of the Peloponnesian Wars (section 82), Thucydides (Hobbes translation) describes the behavior of the different political factions during the revolt in Corcyra in 405 BC:

The cause of all this is desire of rule, out of avarice and ambition; and the zeal of contention from those two proceeding. For such as were of authority in the cities, both of the one and the other faction, preferring under decent titles, one the political equality of the multitude, the other the moderate aristocracy; though in words they seemed to be servants of the public, they made it in effect but the prize of their contention: and striving by whatsoever means to overcome, both ventured on most horrible outrages, and prosecuted their revenges still farther, without any regard of justice or the public good, but limiting them, each faction, by their own appetite: and stood ready, whether by unjust sentence, or with their own hands, when they should get power, to satisfy their present spite. So that neither side made account to have any thing the sooner done for religion [of an oath], but he was most commended, that could pass a business against the hair with a fair oration. The neutrals of the city were destroyed by both factions; partly because they would not side with them, and partly for envy that they should so escape.

The full passage from which this quotation was taken can be be viewed below (front page quote in bold):

The cities therefore being now in sedition, and those that fell into it later having heard what had been done in the former, they far exceeded the same in newness of conceit, both for the art of assailing and for the strangeness of their revenges. The received value of names imposed for signification of things, was changed into arbitrary. For inconsiderate boldness, was counted true–hearted5 manliness: provident deliberation, a handsome fear: modesty, the cloak of cowardice: to be wise in every thing, to be lazy in every thing. A furious suddenness was reputed a point of valour. To re–advise for the better security, was held for a fair pretext of tergiversation. He that was fierce, was always trusty; and he that contraried such a one, was suspected. He that did insidiate, if it took, was a wise man; but he that could smell out a trap laid, a more dangerous man than he. But he that had been so provident as not to need to do the one or the other, was said to be a dissolver of society, and one that stood in fear of his adversary. In brief, he that could outstrip another in the doing of an evil act, or that could persuade another thereto that never meant it, was commended. To be kin to another, was not to be so near as to be of his society: because these were ready to undertake any thing, and not to dispute it. For these societies were not made upon prescribed laws of profit, but for rapine, contrary to the laws established. And as for mutual trust amongst them, it was confirmed not so much by divine law, as by the communication of guilt. And what was well advised of their adversaries, they received with an eye to their actions, to see whether they were too strong for them or not, and not ingenuously. To be revenged was in more request than never to have received injury. And for oaths (when any were) of reconcilement, being administered in the present for necessity, were of force to such as had otherwise no power; but upon opportunity, he that first durst thought his revenge sweeter by the trust, than if he had taken the open way. For they did not only put to account the safeness of that course, but having circumvented their adversary by fraud, assumed to themselves withal a mastery in point of wit. And dishonest men for the most part are sooner called able, than simple men honest: and men are ashamed of this title, but take a pride in the other.

The cause of all this is desire of rule, out of avarice and ambition; and the zeal of contention from those two proceeding. For such as were of authority in the cities, both of the one and the other faction, preferring under decent titles, one the political equality of the multitude, the other the moderate aristocracy; though in words they seemed to be servants of the public, they made it in effect but the prize of their contention: and striving by whatsoever means to overcome, both ventured on most horrible outrages, and prosecuted their revenges still farther, without any regard of justice or the public good, but limiting them, each faction, by their own appetite: and stood ready, whether by unjust sentence, or with their own hands, when they should get power, to satisfy their present spite. So that neither side made account to have any thing the sooner done for religion [of an oath], but he was most commended, that could pass a business against the hair with a fair oration. The neutrals of the city were destroyed by both factions; partly because they would not side with them, and partly for envy that they should so escape.